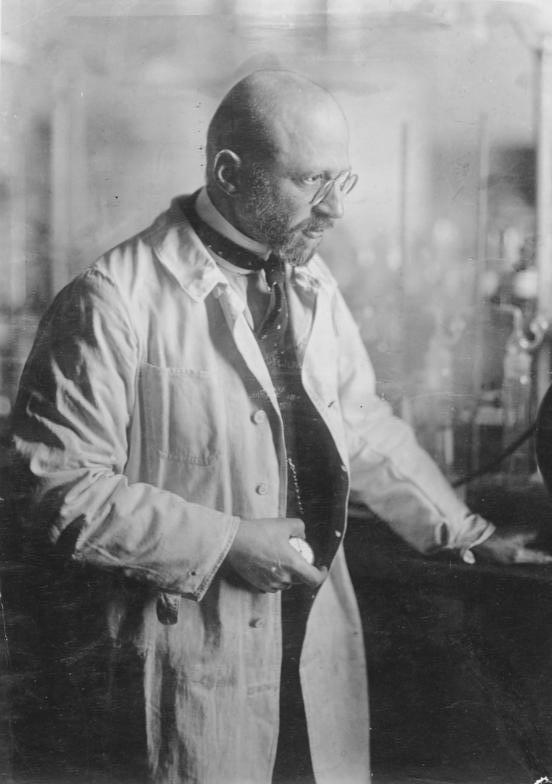

It is Good Friday, 2 April 1915. On the heath between Leopoldsburg and Meeuwen, a hissing noise breaks through the morning silence. Seconds later, a yellow-green cloud crawls painfully slowly over the poor training grounds. Sheep and dogs that are bound here and there on wooden poles, creep when the mist reaches them. Fritz Haber, a German top chemist, values the effects of his chlorine gas from a distance, he can hardly contain his enthusiasm. Haber suddenly sends his horse into the mist. “He gets caught and sees white as wax,” a German officer describes the scene. The demonstration in the Camp Beverlo takes away the last doubts. The chlorine gas will be used on the western front.

The tests have everything to do with an attempt by the Germans to break the stalemate on the western front. Colonel Max Bauer therefore contacts Fritz Haber at the end of 1914, who at that time is already a well-known chemist and director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin. His first plan is to fill shells with explosives and tear gas. However, a test on the Eastern Front failed: it is too cold for the gas to really work. Haber then proposes to use cylinders, which is much more practical to release a concentrated gas. Haber proposes to use chlorine gas because it is already being produced on an industrial scale by Bayer. Chlorine gas is much heavier than air, stays close to the ground and sinks into the trenches where it collects at the bottom. Over time, it spreads in the air and attacking soldiers can advance without having to be afraid of the gas.

The German General Staff is initially concerned about the ethical objections to such a gas attack, but is assured that it is technically not contrary to the Hague Convention because the poison gas does not come from projectiles but from cylinders. And so it is decided to continue planning the gas attack. The place of attack was quickly found: Ypres.

The German General Staff is initially concerned about the ethical objections to such a gas attack, but is assured that it is technically not contrary to the Hague Convention because the poison gas does not come from projectiles but from cylinders. And so it is decided to continue planning the gas attack. The place of attack was quickly found: Ypres.

This article is also available in

![]() Nederlands

Nederlands